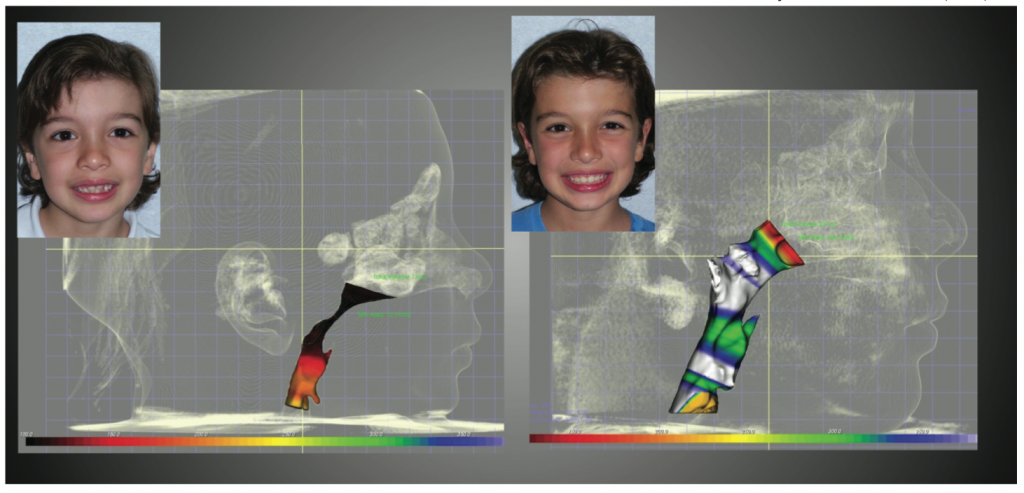

Figure 1: (Top) The patient was a severe sleep apneic with an AHI = 52 and CPAP dependent. (Bottom) The patient received orthodontic treatment and an FDA-cleared sleep oral appliance as a retainer. Post-treatment and retainer, the patient’s AHI score decreased to 5.8.

A team of orthodontists has developed a strategy to effectively implement treatment of obstructive sleep apnea into a practice and improve patients’ lives

By Terry D. Carlyle, DDS, MSc, FRCDC; Louis Chmura, DDS, MS; Paul L. Damon, DDS; Nelson Diers, DDS, MS; David Paquette, DDS, MS, MSD; Juan-Carlos Quintero, DMD, MS; W. Ronald Redmond, DDS, MS; and Bill Thomas, DDS, MS

Each of us has our own story to tell about sleep apnea. We all know someone who snores, struggles to breathe while sleeping, or has even been diagnosed with sleep apnea. If together we are able to make a total health difference in the lives of someone we know and love—particularly, someone suffering from sleep apnea—would the effort be worth it? We were convinced that it would be and, working with Henry Schein Orthodontics, we came together to create the Orthodontic Sleep Apnea Clinical Advisory Team to design a strategy that broadens the scope of the orthodontic practice and is implementable for orthodontists to effectively screen, test, and treat patients for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

“Pursuing an initiative of this nature is in direct alignment with one of Henry Schein’s core values of ‘doing well by doing good,’?” says Ted Dreifuss, vice president of global sales and marketing, Henry Schein Orthodontics. “We recognized a significant unmet healthcare need and acknowledged that only a small percentage of the OSA population is being diagnosed, with an even smaller percentage receiving treatment. We also realize that current treatment options (CPAP, or continuous positive airway pressure) are not satisfactory for most people. We presented the hypothesis that changes to the oral environment could have a positive and lasting impact on the airway and sleep apnea.”

Our team embarked on a mission nearly 2 years ago to determine if there might be an orthodontic component to the problem of sleep apnea, and if so, what orthodontists could do to address the problem with their patients. Here is the mission we agreed on:

To identify and develop the products and protocols to enable orthodontists to improve the lives of people who suffer from obstructive sleep apnea. Our goal is to provide an easier, more efficient route to diagnosis, and treatment of symptoms that yield positive airway changes with more durable results. The Orthodontic Sleep Apnea approach will be a complete system, intended to establish a new standard of care and an expanded healthcare role for the orthodontists.

Figure 2: Diagnosed with a severe airway obstruction, the 8-year-old patient was treated with a combination of ENT surgery and orthodontic treatment. Photo courtesy of Juan-Carlos Quintero, DMD, MS

For some of us, our involvement is personal. Lou Chmura, DDS, MS, was diagnosed with sleep apnea in 2005. He often tells his own personal story of struggling with sleep apnea, how he has undergone multiple treatments over the years, and understands the debilitating nature of the disease.

For David Paquette, DDS, MS, MSD, it was his father-in-law, a severe sleep apneic, who sparked his interest in treating sleep apnea (Figure 1), while Juan-Carlos Quintero’s 8-year-old son changed his practice philosophy. Through CBCT, Quintero diagnosed a severe airway obstruction that had been missed by his son’s medical team.

“I was committed to try to ‘grow’ his airway through a combination of ENT surgery and orthodontic treatment and improve his life,” says Quintero, DMD, MS. “The results were mind-boggling and speak for themselves (Figure 2). Not only did I improve his life, but changed the way I practice orthodontics and the way I speak to my patients.”

Patient Awareness and Market Demand for Sleep Apnea Treatment

Obstructive sleep apnea is an exciting area for orthodontists to be involved in now. The level of awareness of sleep apnea and related health issues is growing rapidly. Public figures such as Reggie White, Shaquille O’Neil, John Candy, William Shatner, and Sylvester Stallone have been in the news and are bringing the topic of sleep apnea to the forefront. Television stations are regularly running public segments on sleep apnea awareness and encouraging patients to be screened, tested, and treated if they have signs or symptoms of this disorder.

It is important to realize that our patients now are coming into our offices aware of sleep apnea, and what would be a casual, patient conversation may lead to a positive discussion about how an orthodontist could help in the process of treating and alleviating sleep apnea.

Understanding Obstructive Sleep Apnea

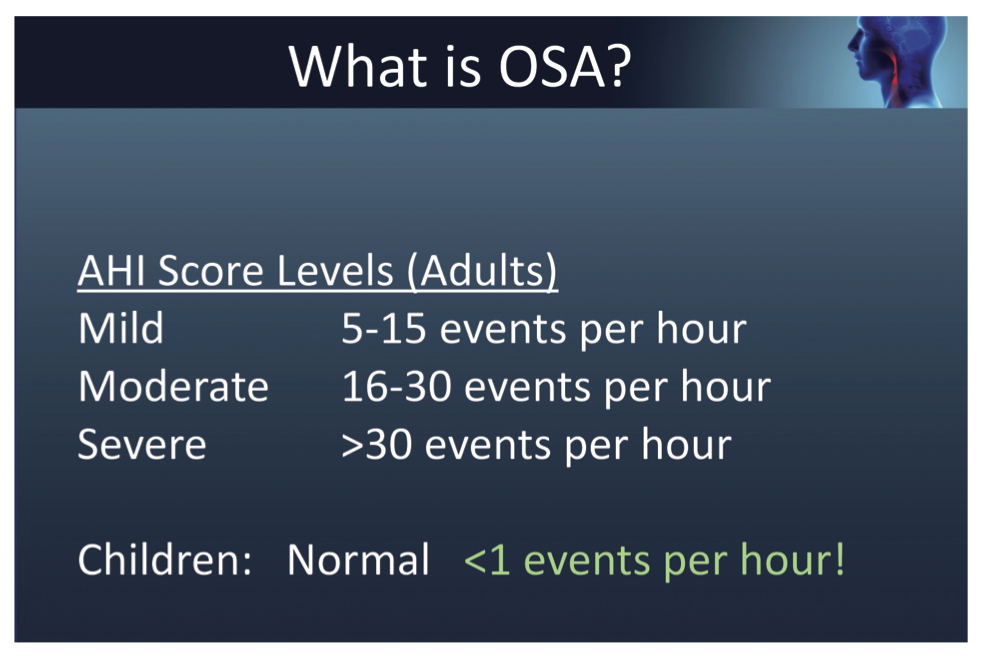

Figure 3: The apnea-hypopnea index, or AHI, is used to measure the number of times that breathing pauses or severely slows per hour of sleep.

OSA is essentially a physical obstruction of the upper airway. Normal sleep involves the air passing through and going directly down to the lungs. With an obstructed airway, the structures in the back of the throat (the tongue, the tonsils, and/or adenoids) occlude the airway and prevent the air from passing.

Patients with OSA experience repetitive episodes of obstruction of the upper airway, causing a loss of breath and oxygen, for anywhere from 10 to 30 seconds or longer per episode. When this occurs, blood oxygen levels drop, and heart rate and blood pressure rise. The brain ultimately sends a distress signal that partially or fully wakes the person and alerts the body to breathe, causing the patient to gasp for air.

The standard OSA severity measuring system is called the apnea-hypopnea index, or AHI, which uses the number of events (or episodes) per hour a person experiences while sleeping to score OSA severity (Figure 3). For example, a normal AHI score for children is less than one event per hour.1

If OSA is untreated, the insult to the body is quite remarkable. Studies show that serious risks of OSA include stroke,2 heart attack,3 obesity,4 diabetes,5 and motor vehicle accidents.6

The Wisconsin Cohort Study (1,522 subjects) documented up to a 35% reduction in 18-year life expectancy for severe apneics.7

OSA is emerging as one of the most prevalent health issues in the United States, and is known to affect more than 18 million Americans, including men, women, and children—85% of whom are undiagnosed.8,9 Children with sleep breathing disorder symptoms suffer from behavioral problems and lower IQ scores.9,10 In addition, studies show that OSA is a chronic, progressive disease with hereditary factors.11 The OSA genetic component alone opens the door for orthodontists to screen and treat entire families in the practice.

Current Routes to Diagnosis and Treatment

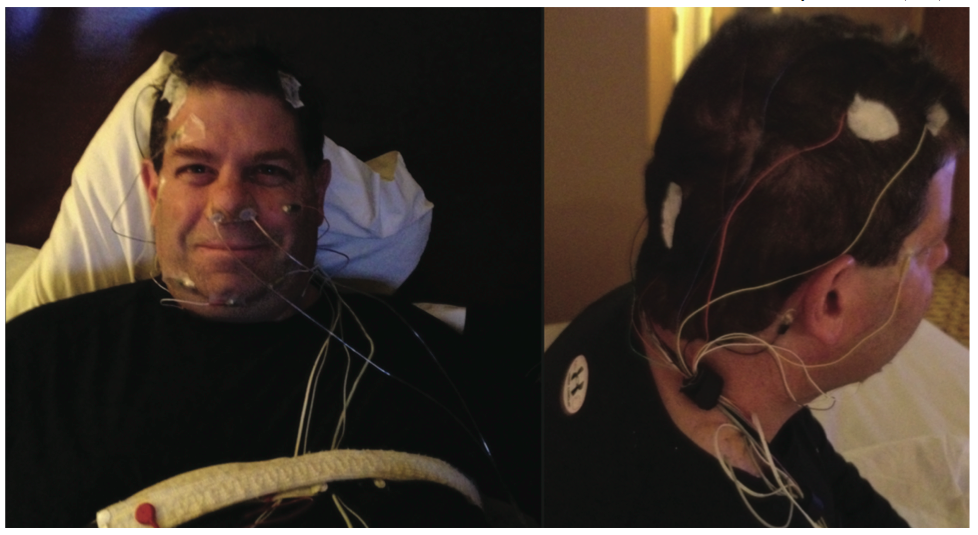

Conventional OSA testing is done through a Polysomnogram (PSG), which means an overnight stay in a sleep laboratory. The patient is wired with many connectors (Figure 4) and observed through the night by a sleep technician. PSGs are oftentimes time-consuming, invasive to the patient, and expensive. A large percentage of patients referred for a PSG never show up for their study. While some cases—patients with significant co-morbidities—may require a PSG, for many OSA cases there must be a more efficient, patient-friendly, and less expensive route to testing.

Figure 4: Here, Lou Chmura, DDS, MS, undergoes a polysomnogram to diagnose his obstructive sleep apnea. Photo Courtesy of Lou Chmura, DDS, MS

The OSA treatment most prescribed by physicians today is the CPAP machine, which can be effective for treating moderate to severe OSA when used as prescribed. However, CPAP users have up to a 70% noncompliance rate due to the discomfort of the mask and machine, the significant social impact, potential inhibition of midface development (in children), and side effects such as headaches and dry nose and throat. In fact, many patients cannot tolerate CPAP therapy, and ultimately, CPAPs do not address the underlying cause of OSA.

Surgical treatment options can be effective, particularly in children (T&A), especially when combined with maxillary expansion and lifestyle changes (weight loss, etc). Combining orthodontics with mandibular advancement (MA) or maxillomandibular advancement (MMA) has been shown to be one of the most successful management strategies for OSA.17,20,21 However, the most commonly recommended surgery—uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP)—not only includes the typical major surgery risks, but is costly, painful with lengthy recovery times, and has a high recurrence rate.

The current medical approach presents significant barriers in the form of time, inconvenience, and cost. The referral process includes a patient visiting the primary care physician, then a sleep physician and/or ENT, completing a PSG, and in the end, the patient will most likely also receive a CPAP machine.

Discovering an Orthodontic Strategy

Why should orthodontists consider treating sleep apnea? Orthodontists see a lot of people with airway problems and have been trained in facial growth, development, and airway, so orthodontists are ideally suited to screen for problems. Orthodontists are the qualified healthcare professionals to identify and treat craniofacial abnormalities and guide the growth of the craniofacial complex to structurally address the symptoms of OSA.

Together, we studied sleep apnea, its tremendous health problems, invasive and costly methods, and uncomfortable treatment options. We were inspired by the amount of medical literature about sleep apnea, little of which had been published in the orthodontic industry. We then asked an important question: Are there orthodontic approaches to OSA that simplify the testing and treatment, and provide a better experience and outcome for the patient?

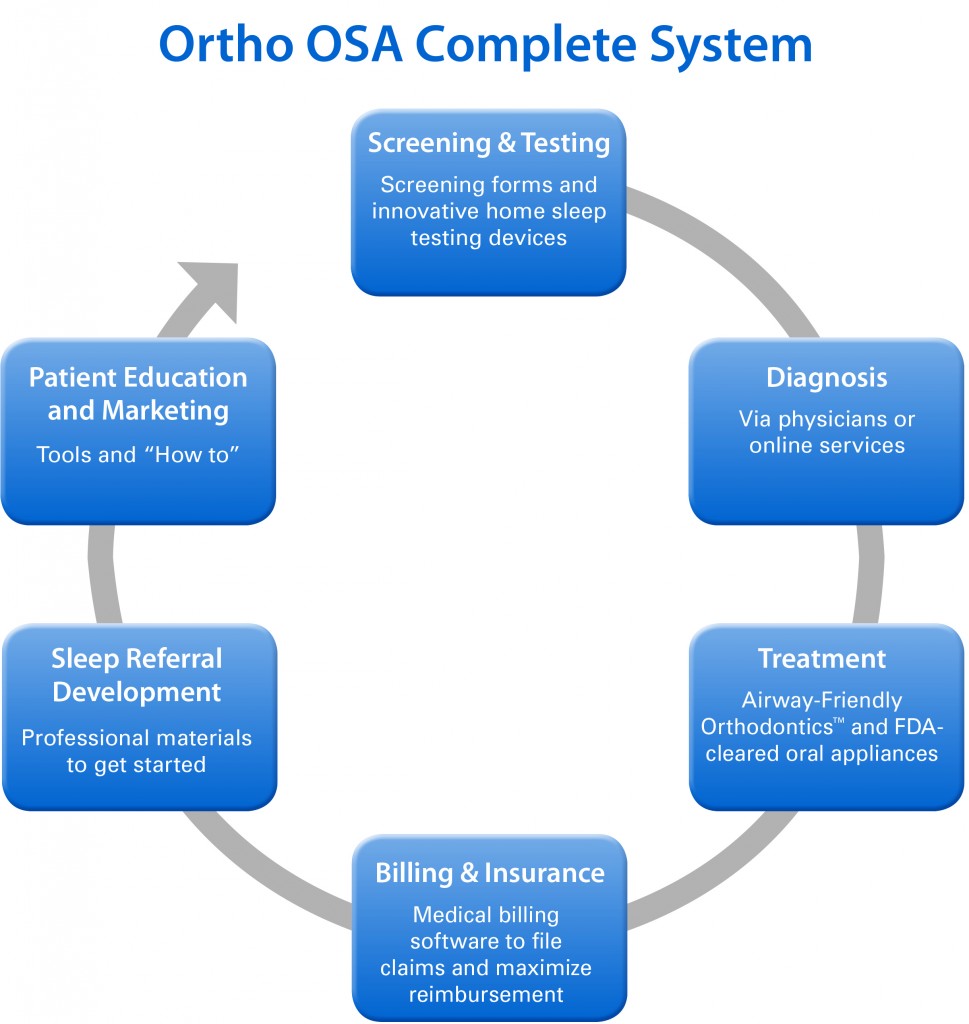

Figure 5: The Orthodontic Sleep Apnea Clinical Advisory Team, working with Henry Schein Orthodontics, created the above strategy to provide orthodontists with an understanding of the physiology of sleep apnea and the current diagnostic and treatment options, as well as a new orthodontic approach, its protocols, and product options.

During our due diligence, we discovered that OSA is a medical problem with orthodontic treatments. Approximately 50% of OSA cases involve the bony structure that surrounds the airway, and by modifying the bony structure (upper arch expansion, advancing the mandible), the orthodontist may be able to address the underlying cause of the condition. With the right information and tools, the orthodontist is ideally positioned to identify and potentially prevent sleep-related breathing disorders in children, and perhaps reverse the condition in adolescents and adults.

Certain key technology developments supported our strategic direction. Maxillary expansion (RME and SME)12,13,14 and maxillomandibular advancement15 procedures have been reported to help normalize tongue position, reduce nasal airway resistance, and decrease or eliminate OSA symptoms.

In 2006, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine stated that oral appliances could be used for the first line of treatment for sleep apnea for mild to moderate cases, and for patients who are CPAP intolerant.16 Research has been published showing mandibular advancement devices open the airway and can provide immediate relief.17,18 Home sleep tests now enable people to test for OSA in the comfort of their own homes and are often covered by third-party insurance. Software applications for record keeping and medical billing simplify the process for integrating sleep into the practice.

In addition, we are in alignment with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) professional organization standards. In 2012, the AAP stated that all children and adolescents should be screened for snoring, and any child with symptoms of OSA should be referred for a sleep study. These new guidelines emerged since research suggests delayed diagnosis of childhood sleep apnea “can result in severe complications if left untreated.”19

Orthodontic Strategies for Sleep Apnea: Education Program and Complete System

Working in partnership with Henry Schein Orthodontics, our Orthodontic Sleep Apnea Clinical Advisory Team designed the first-of-its-kind, 2-day educational course and comprehensive, evidence-based system to implement sleep apnea treatment in the orthodontic practice. The program provides an understanding of the physiology of sleep apnea and the current diagnostic and treatment options, as well as a new orthodontic approach, its protocols, and product options (Figure 5). The orthodontic approach is intended to provide patients with immediate relief from OSA, as well as changes to the airway that may address an underlying cause. We demonstrate innovative technologies and convenient, cost-effective processes to improve the diagnostic and treatment experience.

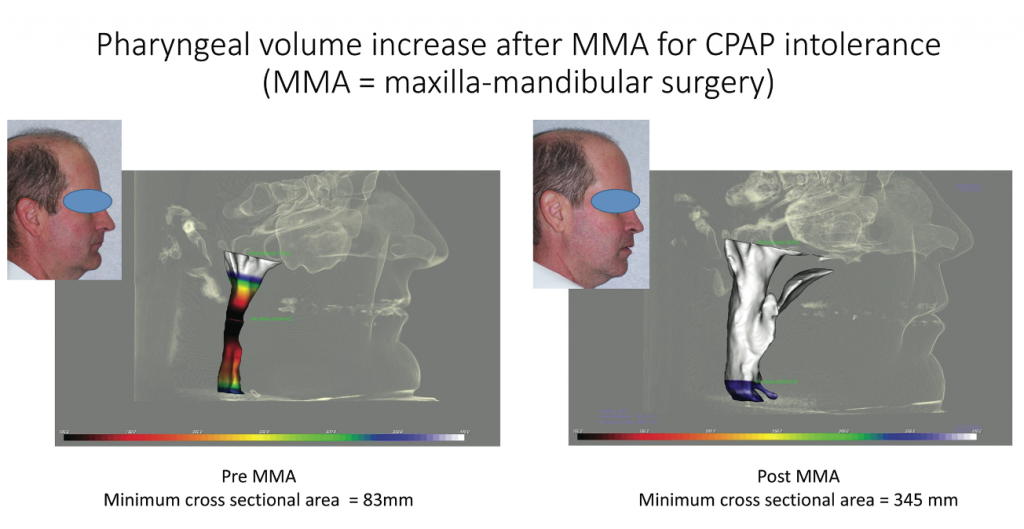

Figure 6: The patient underwent maxillamandibular surgery due to CPAP intolerance. Pre-MMA, the minimum cross sectional area equaled 83 mm (left). Post-MMA, the minimum cross sectional area was 345 mm, increasing the pharyngeal volume (right). Photo courtesy of Juan-Carlos Quintero, DMD, MS

We believe it is important to screen every patient, regardless of age, and ask the critical questions to take the best possible care of our patients. We gather sleep apnea histories and complete medical exams, and when appropriate, send our patients home with high-quality home sleep testing devices. Once we recognize the possibility of a sleep breathing disorder, we refer patients to sleep specialists to gain their definitive medical diagnosis and work together to ensure optimal patient treatment.

As orthodontists, we are uniquely positioned to expand the airway through slow or rapid maxillary expansion (RME/SME), combined orthodontics with mandibular advancement, or maxillomandibular advancement (Figure 6), and sleep apnea oral appliances. Many of us use software that organizes and manages patient documentation, referrals, and medical billing for sleep apnea treatment. We also designed a starter plan on how to incorporate OSA into the practice.

Figure 7: Before beginning treatment using an FDA-cleared sleep oral appliance, the patient had an AHI = 45. Post-treatment, the patient was retested and his sleep apnea score had dropped to -1. Photo courtesy of Lou Chmura, DDS, MS

Making a Difference

The goal is to give patients options and improve their lives, as Chmura did with his patient JC. In 2006, JC came into Chmura’s office showing signs and symptoms of sleep apnea. He had tried a CPAP and told Chmura that he felt like he was “choking” as he fell asleep. He explained that he had not slept more than 4 hours per night since the age of 17 (that’s 35 years; he’s 52 now). His wife reported heavy snoring and that JC stopped breathing while he slept. Chmura treated JC with an FDA-cleared sleep oral appliance. After sleeping with the appliance, Chmura retested JC, and to his amazement, his sleep apnea score dropped from severe (AHI = 45) to normal (AHI = -1) (Figure 7).

Integrating sleep into the practice doesn’t happen overnight, but the process has been inspiring and worth the effort. Especially when patients thank us for giving them better health, more energy, and often better relationships at home. Our motto is, “Breathe, Smile, Thrive.” We are excited about the future of the orthodontic practice, and are convinced that as an orthodontic community, we can make a total health difference in the lives of our patients. OP

—

References

1. Chan, M.D., Edman, M.D, Koltai, M.D. (2004) Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Children, American Family Physician. 69(5):1147-1155.

2. (April 2010) Sleep Apnea Tied to Increased Risk of Stroke, National Institutes of Health

3. Shahrokh – Javaheri, M.D. (2013). Basics of Sleep Apnea and Heart Failure, CardioSource

4. Fritscher LG1, Mottin CC, Canani S, Chatkin JM, Jan. 2007. Obes Surg. 17(1):95-9. Obesity and obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: the impact of bariatric surgery.

5. Brooks B, Cistulli PA, Borkman M, Ross G, McGhee S, Grunstein RR, Sullivan CE, Yue DK (Dec. 1994) Obstructive sleep apnea in obese noninsulin-dependent diabetic patients: effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on insulin responsiveness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 79(6):1681-5.

6. (Aug. 1988) Am Rev Respir Dis., 138(2):337-40

7. Terry Young, PhD, Laurel Finn, MS, Paul E. Peppard, PhD, Mariana Szklo-Coxe, PhD, Diane Austin, MS, F. Javier Nieto, PhD, Robin Stubbs, BS, and K. Mae Hla, MD (Aug 1, 2008). Sleep Disordered Breathing and Mortality: Eighteen-Year Follow-up of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort: Sleep, 31(8): 1071–1078.

8. 18 million, 85% undiagnosed: (2002) Sleep in American Poll, National Sleep Foundation

9. Bonuck, PhD, Freeman, DrPHb, Chervin, MD, MS, Xu, PhDa (March, 2012) Sleep-Disordered Breathing in a Population-Based Cohort: Behavioral Outcomes at 4 and 7 Years, American Academy of Otolaryngology — Head and Neck Surgery. New York’s Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Pediatrics, (doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1402)

10. (2006) Childhood Sleep Apnea Linked to Brain Damage, Lower IQ, Johns Hopkins Medicine

11. (Apr 2009) Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: From Phenotype to Genetic Basis, Current Genomics 10(2): 119–126.

12. Pirelli P, Saponara M, Guilleminault C., (June 2004). Rapid maxillary expansion in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, Sleep 27;(4):761-6

13. Villa MP, Rizzoli A, Miano S, Malagola C. (May 2011) Efficacy of rapid maxillary expansion in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: 36 months of follow-up. Sleep Breath 15(2):179-84.

14. Cistulli PA, Palmisano RG, Poole MD (December 1998) Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome by rapid maxillary expansion. Sleep 21(8):831-5

15. Guilleminault, Holty (2010), Surgical Options for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Med Clin N Am 94, 479-515

16. Clete A. Kushida, MD, PhD, et al. (2006) Practice Parameters for the Treatment of snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apneas with Oral Appliance; An Update for 2005. SLEEP, Vol. 29, No. 2

17. Chad M. Ruoff, Christian Guilleminault. (April/May 2011) Orthodontics and sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Breathing 16:271-273

18. Kathleen A. Ferguson, MD, Rosalind Cartwright PhD, Robert Rogers, DMD, Wolfgang Schmidt-Nowara, MD. 2006. Oral Appliances for Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Review. SLEEP, Vol. 29, No. 2.

19. (2012) Diagnosis and Management of Childhood Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome, PEDIATRICS Vol. 130 No. 3, pp. 576 -584Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: From Phenotype to Genetic Basis

20. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C (1993), Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: A Surgical Protocol for Dyanamic Upper Airway Reconstruction, J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. July;51(7):742-7: discussion 748-9

21. Lye, BDS, MDS, Waite, MPH, DDS, MD, Meara, DMD, MD, Wang, PhD (May 2008). Quality of Life Evaluation of Maxillomandibular Advancement Surgery for Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Volume 66, Issue 5 , Pages 968-972