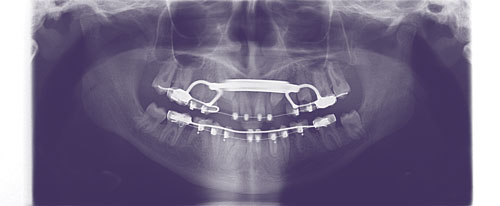

Progress panorex of patient with Down syndrome (DS) illustrating several common dental anomalies— congenital absence is 20 times more likely; impacted teeth (excluding third molars) is 10 times more likely; and maxillary transverse hypoplasia affects 65% of patients.

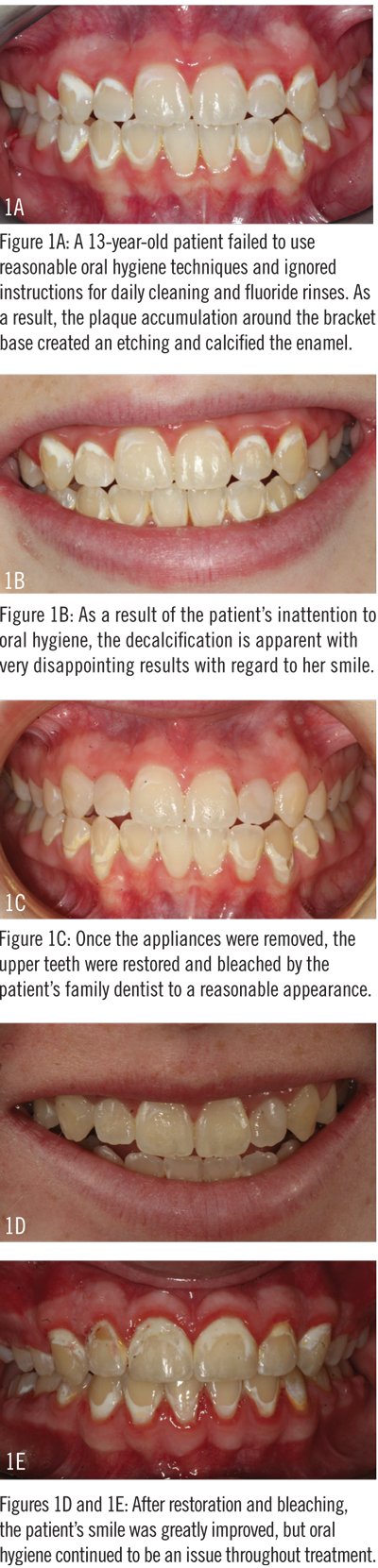

It goes without saying that orthodontists and staff routinely discuss with patients the importance of oral hygiene during and after treatment. How to brush, how to floss, what foods to avoid, etc, are all elements of the typical oral hygiene conversation.

However, this discussion changes significantly if the patient has special needs. Individuals with disabilities such as Down syndrome, autism, or cerebral palsy require orthodontists and their staff to focus on a whole different set of issues when it comes to oral hygiene.

According to David Musich, DDS, MS, of Busch & Musich Orthodontics, Schaumburg, Ill, when orthodontists have the discussion about oral hygiene with a special needs patient, the overall message is the same as with other patients, but with some added focus. For example, he notes that it’s important to make sure the patient and caregivers plan for the additional time it will take to brush teeth and clean the appliances. They should understand the sensitivity issues that come with wearing braces, as well as clearly communicate to the patient and the caregiver the repercussions of poor oral health.

Intraoral anterior photograph of a Down syndrome patient showing the adverse effects (decalcification) of poor oral hygiene aggravated further by chronic mouth breathing.

“Patients with disabilities, especially patients with Down syndrome, typically have a variety of challenging dental problems and frequently also have pre-existing heart conditions that can be aggravated by poor oral hygiene,” Musich explains. “The goal of treatment has to include functional improvement and an improvement in the patient’s long-term health. To achieve these goals, both the patient and the caregiver need information, support, and follow-up.”

David Sarver, DMD, Sarver Orthodontics, Vestavia, Ala, has experienced the repercussions of working with a special needs patient who did not prioritize oral hygiene throughout treatment. As Sarver explains, he and his staff were concerned about the patient for quite some time, and ultimately had to make the uncomfortable decision to end treatment prematurely because of poor oral hygiene.

“I had to take the patient’s braces off because he and his caregivers were just letting his teeth rot,” Sarver explains. “It was a difficult discussion to have, but I ultimately informed the child’s parents that their son was better off with a malocclusion than to have no teeth at all. As orthodontists, we have a professional, and moral, obligation to not let a patient ruin his or her teeth—even if that patient is in the last phase of treatment.”

To gain a more defined understanding of a patient’s oral health, many orthodontists collaborate with the patient’s dentist during the term of orthodontic treatment. This practice is useful, Musich says, for determining the oral hygiene status and decay susceptibility from the initial exam.

Partnering with a patient’s primary dentist also may help to establish a feeling of trust for a child with special needs. Oftentimes, if these patients are comfortable with their pediatric dentist, then they may feel they can share that same relationship with their orthodontist.

“The anxiety level these patients have is often an obstacle for them,” says Ken Fischer, DDS, of Ken Fischer Orthodontics, Villa Park, Calif. “When you approach most of these kids, you have to be very cautious; you have to develop a very high level of trust with them. You can’t just walk up to them and say, ‘Open wide. Let me take a look.’ You have to develop a rapport and try to approach them as a friend.”

How Technology Has Helped

Patients with disabilities, understandably, have more obstacles to overcome during orthodontic treatment compared to other patients. Some of these obstacles may even hinder oral hygiene compliance.

As Musich explains, an orthodontic treatment program means these patients have to adapt to the inconvenience and discomfort of intraoral appliances. “Having something affixed in their mouth can trigger an increased sense of anxiety, and these patients may have the urge to tug at the brackets and wires,” he says.[sidebar float=”right” width=”300″]?

The Rewards of Education

In January 2015, the American Association of Orthodontics released a report noting that new technologies in treatment and “the availability of advanced education in caring for special needs patients,” has helped to make a difference in orthodontic care for patients diagnosed with physical, developmental, or emotional challenges.

Increasingly, orthodontists throughout the country are administering treatment to patients with special needs. And, in nearly every instance, these patients require specific considerations. In an effort to provide these patients with what they need in terms of support for care, a number of practices have dedicated significant time to education on the topic.

David Musich, DDS, MS, of Busch & Musich Orthodontics, Schaumburg, Ill, has worked with special education teachers to help himself, his partner, and their staff to better understand the current terminology assigned to children with special needs. “This type of information is often included on the health history as an acronym, such as ADD, ADHD, LD, CP, DS, SB, etc. Each of these types of special needs may require modifications in our treatment protocols and variations in our approach to encourage and to build trust.”

Musich and his partner, Matthew Busch, DDS, routinely invite special education teachers into their office to shadow the doctors and staff for several hours so that they can, as he says, “see what happens in an orthodontic practice.”

“After they shadow us, we have them back for a staff meeting where they provide us with strategies to be successful with each type of special needs patient,” Musich explains. “This approach has been very effective for our office and for our patients.”

Since they began practicing, Musich and Busch have treated between 200 and 400 special needs patients. This patient base consists of children with Down syndrome, autism, epilepsy, cerebral palsy, spina bifida, and ADD/ADHD.

“Currently, the greatest number of our special needs patients have Down syndrome,” Musich adds. “We’ve worked with a local Down syndrome parent community organization for many years. As a result, our staff—both administrative and clinical—have an excellent understanding of the special requirements for these patients. What’s more, we’ve been able to apply that knowledge to other patients with disabilities, which has been very rewarding for everyone.” OP[/sidebar]

What’s more, some patients may have pre-existing speech difficulties, which can be made worse by orthodontic expanders and other intraoral orthodontic devices.

Fischer has also found that many times, patients with disabilities may not have total control of their muscles. “For some kids, their tongue is constantly moving, or their lips are constantly moving, or they may have copious saliva production,” he notes. “All these elements make it difficult to work on the patient.”

Several advancements have been made in orthodontic technology recently that make it not only possible for patients with disabilities such as Down syndrome, autism, or cerebral palsy to receive orthodontic treatment, but that also help to maintain sound oral hygiene practices.

“The emergence of removable clear aligners has advanced not only the treatment options for these patients, but also gives them more control over the state of their oral hygiene,” Fischer says.

The benefit to using clear removable aligners, he explains, is that they enable patients or caregivers to remove the appliance for flossing and brushing. Musich notes that often cerebral palsy patients may have complications because teeth are crowded or poorly aligned. This makes flossing and brushing difficult for these patients and their caregivers. Thus, having the ability to remove the aligners in order to brush and floss the teeth is extremely beneficial.

Not all patients, however, can be treated with clear trays. Musich explains that at his Chicago-area practice, he and his partner, Matthew Busch, DDS, typically treat Down syndrome patients with traditional braces because oftentimes the treatment plan is too complicated for clear aligners. In these instances, they rely on protective sealants or smaller hygienic brackets to make oral upkeep easier on patients and their caregivers.

“Dental supply companies have improved sealing agents that bond to each tooth before the bracket is positioned. This sealant contains fluoride and greatly minimizes the development of white spot lesions,” Musich says. “Another advancement in oral care has been the improvement of electric toothbrushes that help remove plaque between the bracket and the gingival area. After initial instructions, the patient can take over his or her own oral care with these devices.”

Encouraging Success

Unfortunately, even if a patient is capable of brushing, flossing, and consuming a tooth-friendly diet, that doesn’t always mean the child will prioritize oral hygiene. This issue is amplified, somewhat, when the patient has special needs. In some instances, the patient or caregiver may not fully understand the importance of oral hygiene while in treatment, or the patient relies completely on someone else to administer this type of care.

Regardless of the circumstances, it’s critical to convey to patients, independent of whether or not they have special needs, the importance of oral hygiene during and after treatment. Taking into consideration the limitations of patients with disabilities, however, there are several ways a practice can encourage compliance from these individuals.

“Each child, depending on his or her disability, will require a customized approach to creating an effective oral hygiene agenda,” Musich explains. “Support this information exchange with a customized way to handle the oral hygiene needs of the patient. Also discuss the patient’s diet, frequency of sweets, and use of carbonated beverages.”

Musich recommends utilizing resources available from regional and national associations to help develop a plan for compliance. For example, the American Association of Orthodontics, St Louis, offers its Supplemental Orthodontic History Questionnaire—a worksheet of sorts for harvesting information on a patient’s health history.

“We often use the supplemental health history to guide our thoughts,” he explains. “It helps us to convey to patients the fundamental goals of orthodontic treatment. We do our best to promote the goals of optimal function and health, with esthetics as a secondary benefit.”

Musich also suggests doctors create a visual record of a patient’s progress—showing the child photos of his or her own teeth at each appointment so they can see improvement over time. “It’s also important to follow up with feedback at each appointment and provide what we call ‘oral hygiene grades,’?” he says. “You may need an additional discussion if initial training does not accomplish desired results.”

Sound oral hygiene is paramount to the success of orthodontic treatment. When working with patients who have physical, developmental, or emotional disabilities, the topic becomes more complex.

“I would encourage other practitioners to be more open-minded to offering treatment to these patients,” Fischer says. “As orthodontists, we still have to be selective—sometimes children come into our practices and they simply cannot be treated, even with clear, removable trays. But, thankfully, orthodontics has progressed to a state where we have the capabilities to correct some bad bites and improve oral hygiene in the long run. It will be interesting to see what the future holds.” OP

Lori Sichtermann is a freelance writer for ?Orthodontic Products. She can be reached at [email protected].